The story of public transit in Pinellas County is a long one, spanning as far back as 1885. However, in order to tell the full 139-year tale, we had to split it into three parts. So, strap in for a three-part odyssey as we venture back to when mass transit first began on our little isolated peninsula!

A map of Hillsborough County, Florida, 1882

(Courtesy of the University of South Florida)

Strictly speaking, Pinellas County isn’t very old. Formally established on January 1st, 1912, Pinellas became its own county after successfully seceding from Hillsborough County. The reason for the split? Citizens were growing fed up with the lack of paved roads on the peninsula, making transportation a major challenge, especially after rainstorms.

You could say that efforts to improve transportation have always been in the very fabric of Pinellas County. So, let’s take a deep drive back in time and discover how the pioneering public transit systems of the early 20th century would form the foundations of today’s Pinellas Suncoast Transit Authority!

Full Steam Ahead!

Mass transit first arrived in Pinellas County in the late 1880s thanks to the Orange Belt Railway, led by Russian Captain Peter Demens in 1885. The first train of the Orange Belt rumbled into an area near today’s Central Ave and Dr. M.L.K. Jr Street in the late 1880s, locally known at the time as Wardsville. The railway ran from Sanford, near Orlando, all the way to Wardsville, with notable stops in Tarpon Springs, Ozona, Dunedin, Clearwater, Bellair, Largo, and its terminus in soon-to-be St. Petersburg.

Orange Belt Railway train in Pinellas County, with President and General Manager Peter Demens standing on the right.

(Courtesy of Trains Magazine)

The train would thunder down Railroad Avenue, which we know as 1st Avenue South today. It would even travel a couple hundred yards into Tampa Bay on a wharf that’s now known as Demens Landing. Throughout its complicated life, the railway would bring many tourists and future residents to the area.

After a huge portion of the track was left abandoned in the 80s, the remnants of Pinellas’ Orange Belt Railway would become the Pinellas Trail, an impressive 47 miles of beautiful trails for hikers and cyclists to enjoy.

Cyclist riding beneath the railroad-inspired sign on the Dunedin portion of the Pinellas Trail.

(Courtesy of the Pinellas Trail Facebook Page)

Detroit native John C. Williams and Captain Peter Demens established St. Petersburg on June 8th, 1888, with a population of just 300. Despite its small size, it was the biggest area of population on the little peninsula considered West Hillsborough County at the time.

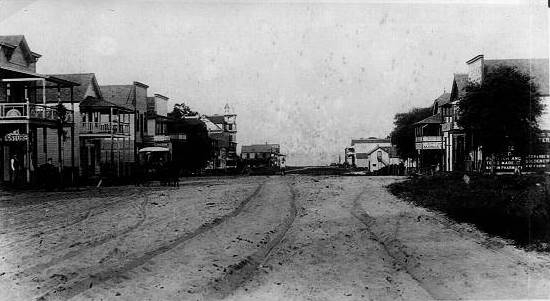

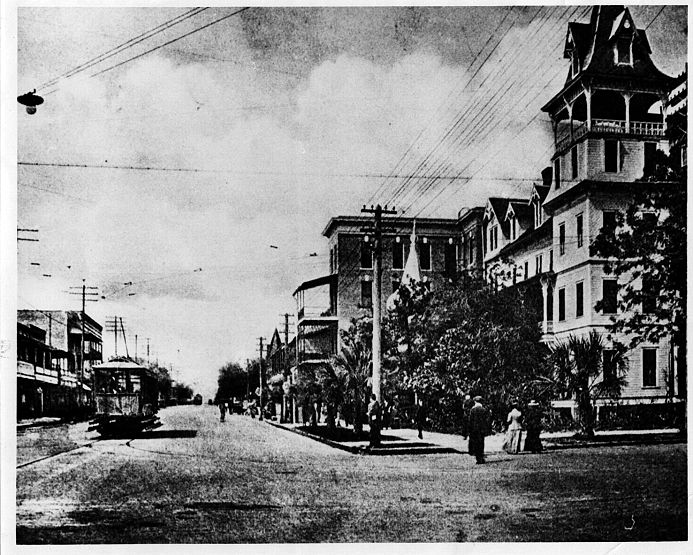

Central Avenue in newly founded St. Petersburg, 1895.

(PSTA Archives)

As the largest development in the soon-to-be Pinellas County, city-wide public transit began on what would one day become Central Avenue. While we may think of buses, trains, and commuter rails as examples of public transit today, the streetcar was king at the turn of the 20th century. In fact, we owe much of the development of St. Petersburg and Southern Pinellas County to the streetcar.

The Era of the Streetcar

The year was 1901, and on New Year's Eve, Philadelphia native Frank Allston Davis would incorporate his newest entrepreneurial pursuit: St. Petersburg and Gulf Railway Company. You see, America was experiencing “Trolley Fever,” as rail-based and cable-hauled streetcars or trolleys were popping up in major cities around the country.

For example:

San Francisco’s cable cars in 1873; Scranton, Pennsylvania, “The Electric City” and their first electric streetcar line; Richman, Virginia’s streetcars of 1888; and Los Angeles’ 1872 electric streetcars that would soon become the longest electric tramway system in the world. Whether folks preferred to call them streetcars or trolleys, these charming open-air vehicles took the country by storm, and Frank A. Davis saw an opportunity for the burgeoning tourist town of St. Petersburg to reap the same benefits as the larger cities. After all, it was the sign of a “modern” city.

Frank Allston Davis

(Public Domain)

Real estate speculators were certainly interested in the idea as a selling point for new properties. So Davis turned to his fellow Philadelphian colleagues to raise the money necessary to begin construction on the trolley line. His friends had good reason to invest, too—Davis is credited for introducing electricity to St. Petersburg by founding the St. Petersburg Electric Light & Power Company in 1899. An electric trolley system seemed to be the perfect next step for Davis.

Among Davis’ investors were fellow Philadelphian Jacob Disston, brother of Hamilton Disston, whose contributions and investments aided in the development of Kissimmee, St. Cloud, Gulfport, Tarpon Springs, and the rapid growth of St. Petersburg. Jacob was eager to invest in a trolley line, as he wished for it to serve his property on the gulf. George Gandy was another big investor whose name is well-known among locals for the southern-most Gandy Bridge.

Next on the agenda was securing a franchise ordinance from the Hillsborough County Commissioners (remember, this was before Pinellas County was established). A franchise ordinance essentially allowed governments to grant exclusive privileges to private individuals or companies to be the sole providers of a good or service. However, obtaining one for his trolley line was fraught with contention and competition from another interurban line being considered between St. Petersburg and Tampa. Eventually, Davis got the terms he wanted after some revisions and squabbling, with the requirement that one mile of track be built within six months and an additional two and a half miles within 18 months.

St. Petersburg & Gulf Railway trolley lines from 1904–1919.

(PSTA Archives)

The Central Avenue Line

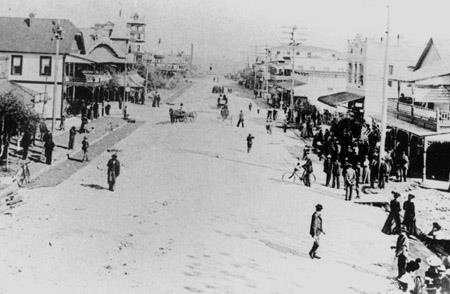

Central Avenue in 1901, before the Central Avenue Line was complete.

(PSTA Archives)

Construction began shortly on the first mile of rail, under the watchful eye of A. P. Weller, a stockholder and manager of St. Petersburg and Gulf Ry. Co. Securing the materials for the rails and a streetcar was difficult, but eventually, Weller prevailed. The first ever streetcar (known as car #1) in St. Petersburg would arrive on November 5th, 1902, shipped via railroad and likely pulled to the tracks by horse or mule. The car itself was bought second-hand, as were the rails and 500-volt DC generator used to power the trolley line.

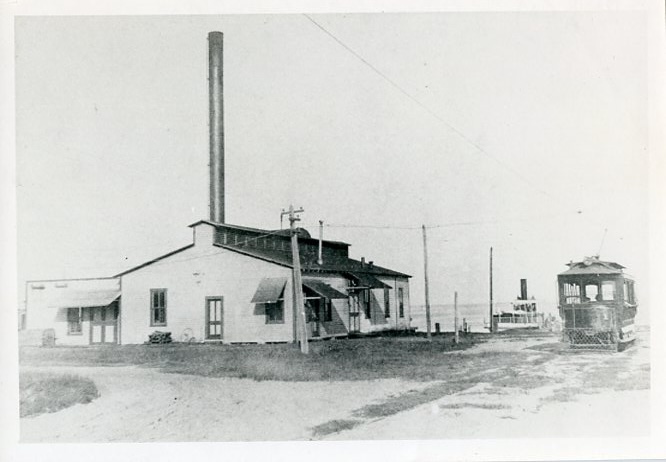

St. Petersburg’s first streetcar (car #1) at the start of Central Avenue next to its powerhouse in 1903.

(Courtesy of the St. Petersburg Museum of History)

Construction had finally begun on the track, but Davis was well behind schedule due to delays in procuring materials and building the powerhouse. They would not meet the six-month deadline, requiring an extension until March 1903. Despite the road bumps in construction, car #1 would make its first trek on Friday the 13th of February, 1903. To modern eyes, the loud squeal of worn wheels on the rusty track and resulting sparks would likely make us cringe. However, residents of St. Petersburg were enthralled by such a modern amenity in their city, gathering to watch and cheer as it rattled ten miles an hour down the small segment of track built so far.

A trolley on Central Avenue in 1905.

(PSTA Archives)

The future was coming to St. Petersburg, and its residents, entrepreneurs, and real estate investors alike saw endless opportunities for the city.

The Disston City Line. Uh… the Veteran City Line. Just kidding, it’s the Gulfport Line.

Although the track was still actively being laid, limited and free service had already begun for car #1. Real estate developers soon asked for extensions to their properties, especially in Disston City (founded by Hamilton Disston and later renamed “Gulfport”) to the southwest. And Davis would need to appease such a request, considering Jacob Disston was the trolley line’s primary investor. Davis obtained another franchise in 1903 to extend the line to Disston City, and the company ordered more second-hand cars from Washington and Baltimore, as well as unpowered trailer cars that could be towed by car #1.

The line to the developing Disston City would take passengers through thriving orange groves and pineapple plantations on its way to Disston Ave (49th Street) and Boca Ciega Bay. As with the Central Ave Line, service began quickly and would take passengers as far as the tracks were finished. During the construction of the line to Disston City, the franchise ordinance was amended to allow an extension to be built in 1904 that went from Booker Creek up Second Street to Florida Avenue (7th Avenue). This section would be operated as part of the Disston City Line.

The Disston City Line would finally be completed in April 1905. However, Disston City was also dead by 1905. Hamilton Disston’s beloved hotel on Boca Ciega Bay was damaged by severe weather damage twice and left abandoned for years, and the wharf next to it was rotting away.

Captain John F. Chase would take over development and change the name to Veteran City. See, Chase wanted to turn the area into a retirement community for Union Civil War veterans, a well-meaning idea not without its skeptics. Nonetheless, the line serving the new Veteran City was in service, and passengers were known to reach out the trolley windows to pick oranges as they clattered through the groves. Trolley crews would spearfish in Veteran City during their 15-minute layover, and fishermen would hang their catches on the car to show them off on their way back into St. Petersburg. What a sight that must have been

Veteran City, as Captain Chase envisioned it, would never materialize. By October 1910, votes would be cast at the Gulf Casino to choose the final name of “Gulfport” and officially incorporate it as a city. The trolley line would be known as the “Gulfport Line” from then on, and Gulfport citizens were grateful for reliable transportation to St. Peterburg, considering the complete lack of roads in the undeveloped area. Prior to the Gulfport Line, getting to St. Pete required either a boat, a treacherous journey through palmetto swamps by mule cart, or a miserable trek on foot trails.

Trolleys entering the Gulfport Line switch, c. 1910.

(PSTA Archives)

Bayboro and Big Bayou

So far, the bulk of St. Petersburg’s growth had expanded northward, where land was easier to develop; to the east and to the south were low-lying, mosquito-infested swamps that would require much effort to develop. However, even further south of these swamps was precious high ground, and C. A. Harvey and Dr. H. A. Murphy had plans to dredge the harbor to fill in the lowlands. They organized Bayboro Investment Co. and started the complicated process of developing the area. Despite opposition from St. Petersburg and Tampa, as well as public disapproval and doubts, they managed to get approval for development, and work began.

But what would this new development matter without a streetcar line to serve it?

At first, Bayboro Company attempted to build and operate a trolley line themselves, even obtaining a franchise ordinance for a track to Pinellas Point on Tampa Bay in November 1906. Construction had begun, and gas motor cars were ordered, but the decision was soon made to have Davis and his St. Petersburg & Gulf Railways operate their electric line there instead.

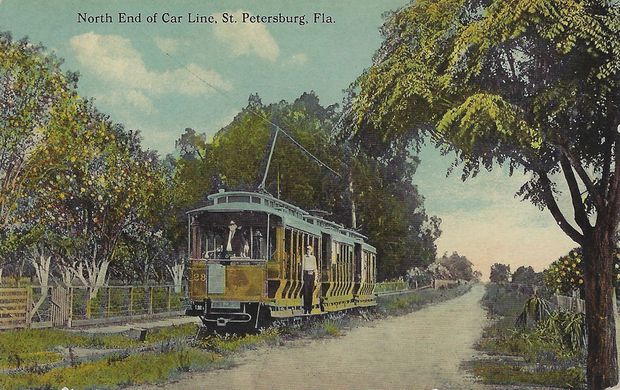

The north end of the trolley line that served the Southside of St. Petersburg to 38th Avenue South.

(Courtesy of Florida Memory)

And thus, the first trip made on the new line would occur on January 5th, 1911. The new Bayboro Line would run from Central Avenue to 15th Avenue (now 17th Avenue) and Bay Street.

With the success of Bayboro and the new trolley line, developments soon popped up even further south when real estate speculator R.R. Kennedy discovered more high ground and paid for a track extension from Bayboro to 38th Avenue S. near Big Bayou and Grandview Park. The line would be opened to the public on Thursday, March 12th, 1914, carrying more than 100 guests who owned property there.

Expansions to Northshore

By this point, Davis and St. Petersburg & Gulf Ry. Co. could languish a bit in their success. When another real estate investor or entrepreneur was paying for the track, all Davis’ company had to do was supply a streetcar and operate the line. The steady stream of nickel fares ($1.60 in today’s money) was plenty to cover the cost of the motorman and the electricity required to run the line.

Of course, that didn’t account for maintenance to the track or cars. Surely that wouldn’t become a problem in a few years…

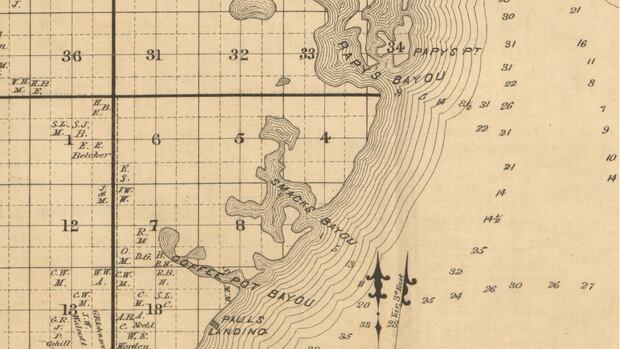

An 1882 map of the North Shore area.

(Courtesy of the University of South Florida)

Development north of downtown St. Petersburg and the Central Line was well underway. C. Perry Snell, a developer who would establish the Snell Isle area, organized the Bay Shore Company with the goal of taming the unmanageable palmetto pastures along the north shore. With homes quickly going up in the area, Snell and his business partner J.C. Hamlett paid for trolley tracks to serve Coffee Pot, Bay Shore, Bay View, and Bay Front. The line, referred to as “North Shore,” was operating down 22nd Ave N by April 1912 and was extended in 1915 to the newly-built baseball park at Coffee Pot Park, where the St. Louis Browns would conduct spring training in their 1914 season.

Another extension contract was created while the Coffee Pot and North Shore area was being developed and the trolley line was being laid. This line would travel up the west side of 9th Street (Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Street N. today) to 34th Avenue North, serving what was considered the Piedmont area at the time.

Jungle Line

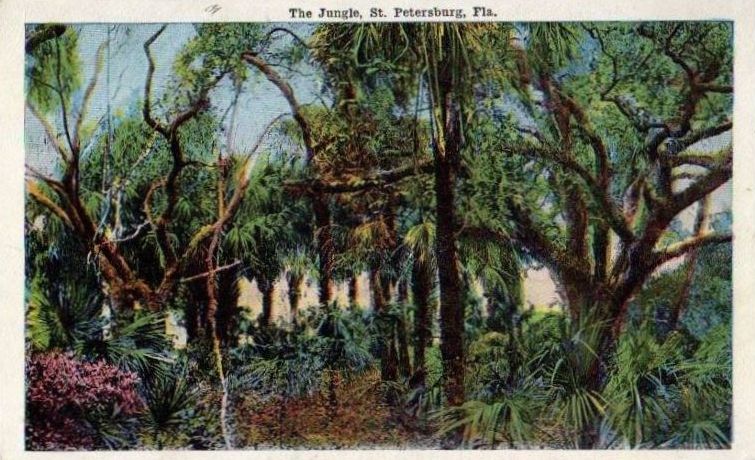

Among all of the early streetcar lines, the Jungle Line is perhaps the most famous. As the Central Line steadily crept to the west throughout the first decade of 1900, developer H. Walter Fuller had a vision for an area he called “The Jungle.” The Jungle is about two square miles on the west end of St. Petersburg, caged between the Pinellas Trail, 5th Avenue N., and Boca Ciega Shores. Today, the Jungle includes the neighborhoods of Jungle Terrace, Jungle Prada, and Azalea Homes, as well as Park Street North.

However, in 1907, the majority of this area was quite literally a jungle—simply a swath of undeveloped palmetto swamps and overall difficult terrain. For this reason, Fuller leaned into the “jungle” name, stating it was a taste of the “real tropics” as a marketing tactic to intrigue investors and tourists.

A postcard of “The Jungle” prior to its development.

(PSTA Archives)

Fuller firmly believed that the future of St. Petersburg's success and the modernization Davis had heralded so far would depend on westward expansion. And, to Fuller, the Jungle was the next big thing for the city. His first goal was to extend the trolley line from bay to bay (Tampa Bay to Boca Ciega Bay), and Davis’ original investors from 1901 were ready to help fund the ambitious project. After securing the land from 9th Street to Boca Ciega Bay, construction began in October 1912, and the full line was finally completed in December 1913. It was marketed with the tagline, “Take Jungle Car and Help Yourself.”

Along the Jungle Line, Park Street would soon be host to many fine homes and, most importantly, fine entertainment. The convenience of the streetcar taking passengers right down the up-and-coming area attracted many winter tourists and wealthy locals alike. The Sunset Hotel would open in 1920 at the corner of Central Avenue and Park Street, and the Jungle Country Club Hotel and Golf Course would open in 1925 (the building is now part of Admiral Farragut Academy).

The decline in sales due to World War I would drive Fuller bankrupt, leaving his St. Petersburg enterprises to his son, Walter P. Fuller. And Walter was committed to continuing his father’s dreams for the Jungle.

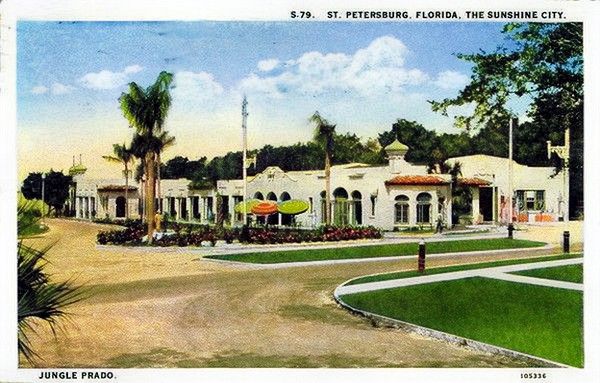

In 1924, Walter built the “Jungle Prado” shopping center at Park Street and Elbow Lane (called the Jungle Prada Tavern today), named after the famous Prado Promenade in Havana. While it was originally named Jungle “Prado,” a St. Petersburg Times article listed it as “Prada” in 1941, and over the years, the name eventually became “Prada” everywhere. Spelling was quite loose back in the day, after all.

A postcard of the Jungle Prado, c. 1925.

(PSTA Archives)

The Jungle Prada also boasted a nightclub called The Gangplank, rumored to have played host to Duke Ellington, Babe Ruth, and even Al Capone. The Gangplank even had its own house band called “Earl Gresh and His Gangplank Orchestra.” And best of all, a recording of their 1925 hit “Help!” still exists today (click here to listen!).

With the convenience of the Jungle Line, the Jungle Prada was the premier shopping and entertainment destination of the time. There’s even local legend that The Gangplank housed a speakeasy during The Prohibition Era (1920–1933).

Without the Jungle Line, West St. Petersburg might have stayed a jungle for much longer!

Trolley Trouble

A streetcar traveling down Central Avenue, looking west from 5th Street, c. 1912.

A streetcar traveling down Central Avenue, looking west from 5th Street, c. 1912.

(PSTA Archives)

World War I brought trouble to St. Petersburg and many of its businesses. Tourism declined while wages and electricity costs increased. St. Petersburg & Gulf Ry. had to spend most of their profits paying their employees, leaving very little for improvements and, most importantly of all, maintenance. Yes, track and car maintenance finally bit the company in the rear.

While the most obvious solution was raising the trolley fares, they legally couldn’t charge more—the state and city governments controlled fares with an iron fist. Davis and his partners had invested their own money into the trolley lines, and although Davis passed away in 1917, his company remained. However, without a viable way to increase income, there was only one option: declare bankruptcy in 1919, putting the entire trolley system up for auction.

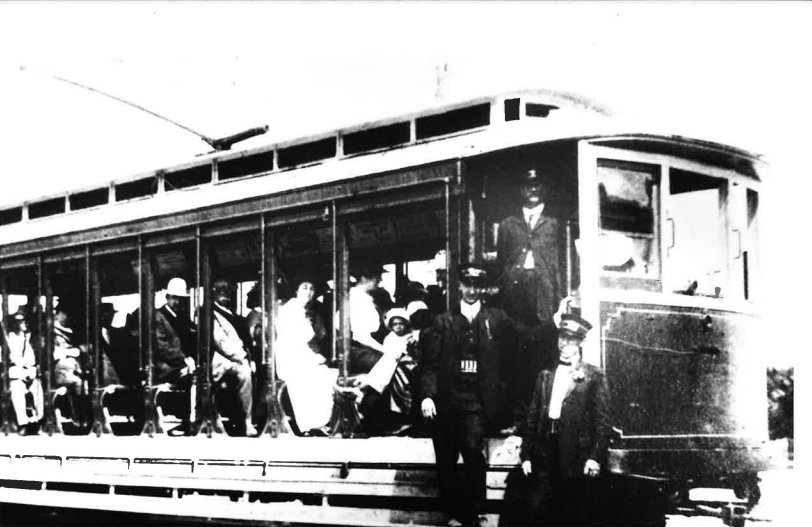

A trolley in 1919.

(PSTA Archives)

The city of St. Petersburg and its founding fathers knew the collapse of the trolley lines would seriously harm tourism returning to the area after World War I concluded. In an extremely bold move for the time, the city chose to purchase the trolley system for its scrap value of $175,000 ($3,336,030 in today’s money), creating the St. Petersburg Municipal Transit System, later known as SPMTS.

The Jungle Trolley.

(PSTA Archives)

As Robert A. Stanton says in his 2006 book “Streetcar to the Jungle: Trolleys in the Streets of St. Petersburg, Florida,” an essential resource for this blog, “It was a bold move, but [105] years later, what remains of every streetcar system on this continent is publicly owned, and new ones are being built each year with government money.”

In many ways, St. Petersburg was already ahead of its time.

With the streetcar system under the city’s control, there was no longer a need to make a profit. However, there was now a trade-off—any improvement or major purchase must be voted on and approved. Only seven cars from the original company would remain, and the city began the process of acquiring new cars and rails.

Over the following decades, route extensions and improvements to trolleys and rails would occur under the city’s ownership. The city was growing rapidly, and although there were now more automobiles on the road after WWI, public transit through the trolley system was still the backbone of the city.

However, there was soon to be a new mode of transit in Pinellas: the bus.

Next Stop: The Bus

In the next installment of The History of Public Transit in Pinellas County, we’ll see how the bus's introduction and the streetcar's unfortunate fate would cause a complete paradigm shift in mass transit for our county.

The drama! The historical intrigue! You won’t want to miss Part 2 of this Deep(er) Drive into the past!

Click here to continue the story!

Sources

Buckley, James. Street Railways of St. Petersburg, Florida. Harold E. Cox, 1983.

Elftmann, Steve. The Jungle Country Club History Project, junglecountryclubhistoryproject.blogspot.com/p/blog-page.html.

Florida Memory, www.floridamemory.com/.

Kile, Monica. “125 Years of Light and Power in St. Petersburg.” I Love the Burg, 17 July 2024, ilovetheburg.com/125-years-of-power-and-light-part-two/.

Kile, Monica. “Remembering St. Pete’s Long-Lost Trolleys.” Northeast Journal | St. Petersburg, Florida Journal | Newspaper, 24 Jan. 2023, northeastjournal.org/remembering-st-petes-long-lost-trolleys/.

Lehman, Robert. “Streetcars in Tampa and St. Petersburg: A Photographic Essay.” Tampa Bay History, Digital Commons @ University of South Florida, 1997, digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1442&context=tampabayhistory.

“Pinellas County Historical Background.” Pinellas County, Dec. 2008, pinellas.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/PCHB.pdf.

Stanton, Robert A. Streetcar to the Jungle: Trolleys in the Streets of St. Petersburg, Florida. 2006.