Welcome back to our Deep(er) Drive, where we tell the long and fascinating story of public transit in Pinellas County.

Warning: spoilers ahead if you haven’t read part 1 (click here to read)!

In the last episode, we explored how railroads brought the first residents to Pinellas County and how Frank A. Davis’ St. Petersburg and Gulf Railway Company got them around town on electric streetcars. From 1900 to the 1940s, the streetcar was king in every major city.

However, as you’ll learn, the time of the trolley was soon coming to a close. There was a new king in town: the bus. So, let’s explore this next era of public transit in Pinellas and see how bus systems became the name of the game!

The Dawn of the Bus

The roaring twenties were well underway. Tourism and real estate were booming in Pinellas County. In fact, real estate in Florida overall was exploding. In the case of Pinellas County, the trolley line had been rescued and improved under the city’s ownership. But all the developing cities of Pinellas were looking for ways to expand their public transit services.

Enter the bus.

The first commercially operated bus in Pinellas County.

The first commercially operated bus in Pinellas County.

(PSTA Archives)

The very first commercial bus in Pinellas County arrived around 1919. It was a six-wheeled vehicle made of two Ford automobiles welded together, providing transportation between St. Petersburg, Clearwater, and Dunedin. In Tarpon Springs, similar vehicles were built to provide regular service for sponge workers in the booming Sponge Docks. Dunedin also began its own bus line to support its multimillion-dollar real estate project, bringing in new buses that could transport up to 20 passengers.

South County relished in the economic boom and increased tourism, no doubt seeing opportunities in the new buses of North County. Soon enough, SPMTS chose to buy eight gasoline-powered buses in May 1926 as an experimental idea to supplement the robust trolley system. They were put into service on June 6th, 1926, running to Lealman as the first-ever bus route. Another route running to Pinellas Park would be added a few years later, in December 1928, followed shortly by another serving the VA Hospital built in Bay Pines.

However, as we all know, the roaring 20s would soon go very quiet.

Florida’s real estate market would collapse in 1927, partly due to the major hurricanes of 1926 and 1928. And then 1929 brought the official start of The Great Depression itself. Tourism died in Pinellas County, and many businesses suffered or went bankrupt entirely. But, despite the challenges, the municipal transit system weathered the rough waters and avoided bankruptcy. In fact, the City of St. Petersburg was happy with the transit system, as it was helping keep the city alive throughout the economic downturn, a sort of tourniquet until the tourists finally returned.

A trolley in 1939, “Seasons Greetings.”

(PSTA Archives)

By 1939, the city expanded the bus system after recommendations from a county-wide survey, emphasizing service in areas that a streetcar could not adequately serve. This year also marked the beginning of World War II; however, its effect on Pinellas County would not be the same as World War I.

Although World War II brought gas rationing and many other restrictions, St. Petersburg was teeming with soldiers that replaced the void left by diminished tourism. The US Army Air Corps had chosen to use the city as a training site, and every hotel (except for the Suwanee Hotel) housed thousands of troops. Even the Vinoy golf course became a tent city for military personnel.

After the conclusion of World War II in 1945, Pinellas County experienced another boom in growth thanks to lifted rations and restrictions. Not to mention, many soldiers who trained in St. Petersburg fell in love with the city and returned after the war to call it home. Construction doubled, and other cities like Clearwater, Dunedin, Pinellas Park, and Gulfport all saw their populations rise. The population even exploded in some areas, such as Bellair, which saw a 340% increase. In post-war Florida, families could now afford cars, homes, and the newest modern appliances of the time.

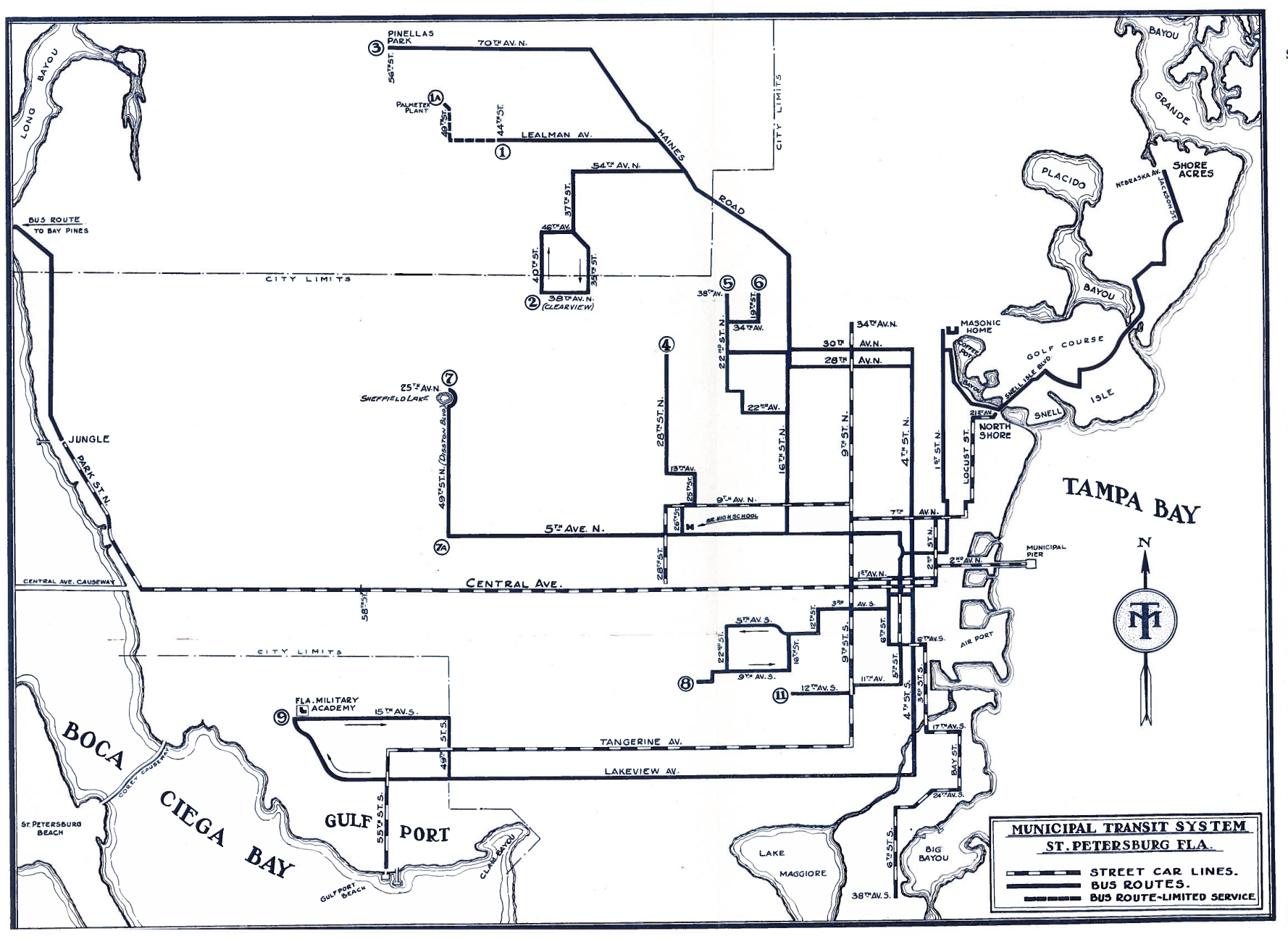

SPMTS system map, showing both street car lines and bus routes in southern Pinellas County c. 1942.

SPMTS system map, showing both street car lines and bus routes in southern Pinellas County c. 1942.

(PSTA Archives)

The Retirement of the Trolley

Urban development was exploding and, for the first time, many people were choosing to live outside the bigger cities in the county. It was the start of the suburban trend that would define huge cities like New York and Chicago. People still worked in the city but craved an affordable, quiet residential community to raise their families. And it was no different in Pinellas County. Shopping centers began popping up in these suburban areas, far from bus or trolley lines, and designed to cater to people with cars. These changes would inevitably affect the trolley and bus lines.

An ugly reality lurked beneath these changes: the streetcar was falling deeply out of style. To mid-century sensibilities, they were unsightly, loud, and, worst of all, antiquated. The overhead lines, poles, and rails were an eyesore to many. Even worse, critics of the trolley complained that their slow speed and bulky cars worsened traffic congestion.

Traffic in St. Petersburg, c. 1950s.

Traffic in St. Petersburg, c. 1950s.

(Courtesy of Roger Wilkerson, The Suburban Legend Blog)

Clearly, the Trolley Fever was over, and the automobile was in. Streetcars were falling out of favor everywhere in America as middle-class families became infatuated with the automobile for its privacy and speed. And families weren’t just buying one anymore—two- and three-car families were becoming the norm by the late 40s.

However, many wouldn’t or couldn’t afford even one car. Public transit was still much needed in Pinellas County. The bus, which had improved since the days of welded Ford vehicles, offered flexibility and wasn’t limited to tracks. It wouldn’t take long for the City of St. Petersburg to begin discussions of replacing the old trolleys with bus routes.

On October 21st, 1947, the decision was made to convert the old transit system to bus routes only. Car #100 would make its final journey to Gulfport on May 7th, 1949, with crowds of people wanting one last ride. A line of automobiles followed it back to the barn, giving the old streetcar the final farewell it truly deserved.

The United States’ southernmost streetcar system was gone.

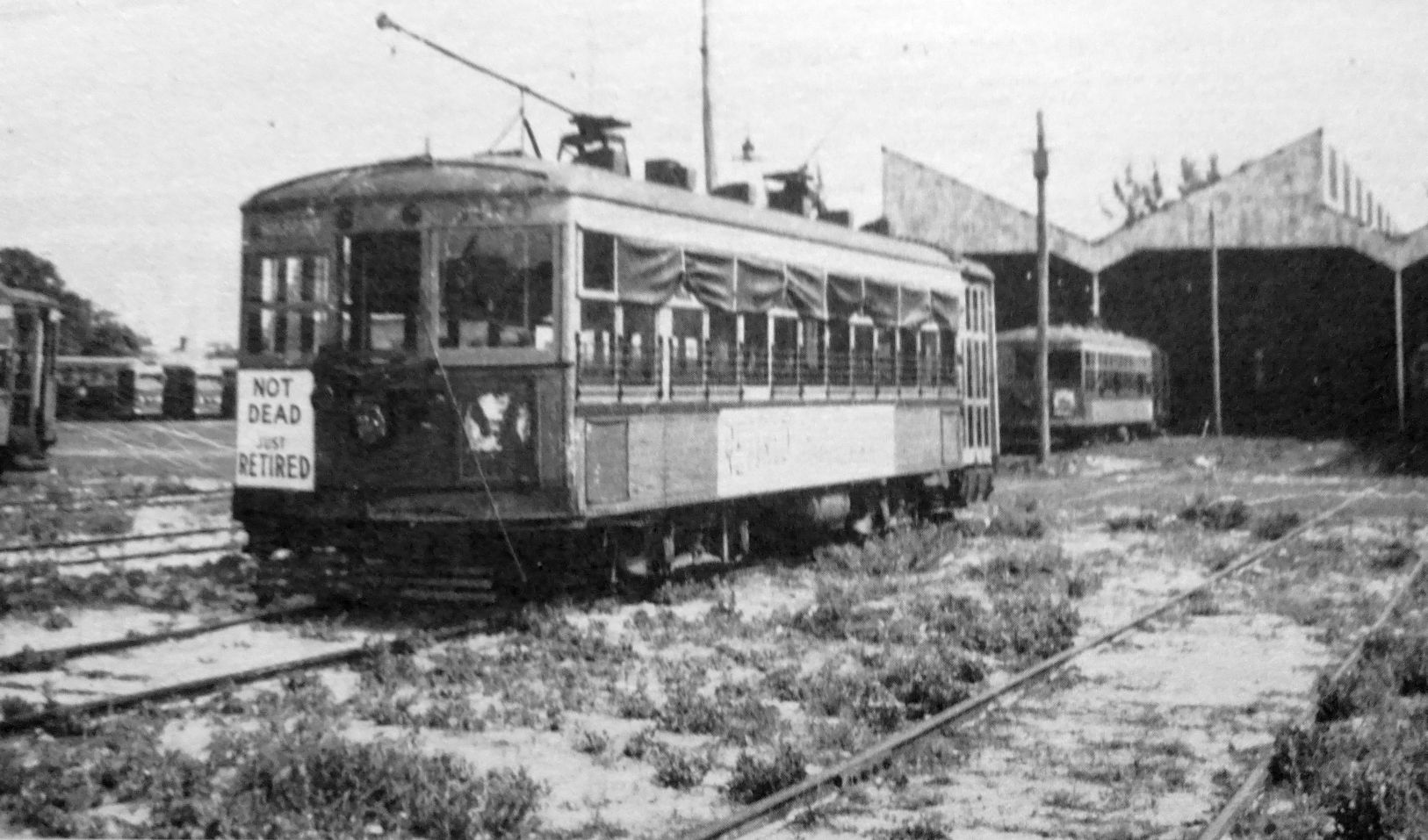

One of the last trolleys. A sign on its front reads: “Not Dead, Just Retired.”

(PSTA Archives)

The Era of the Bus

With the streetcar off to a farm upstate, the St. Petersburg Municipal Transit System (SPMTS) was now a bus-only system, and they soon got to work building out their fleet. While the system had incurred a $800,000 debt ($10,617,383 in today’s money) during its switch from trolleys to all buses in 1948, it paid off the debt in full as profits climbed in a post-war economy. Within ten years, SPMTS went from 67 buses to 103.

The St. Petersburg Municipal Transit System (SPMTS) buses and operators.

(PSTA Archives)

Whereas trolley fares had been a nickel for most of their lifespan, bus fares were 10¢ until 1958, the lowest fare price on Florida’s west coast. From 1945 to 1958, the buses carried 10 million passengers annually, and every route ran to Williams Park in the center of downtown. However, transfer points were constantly being added for passengers who wished for more cross-county travel.

Small, private bus lines began to pop up in other parts of Pinellas County. Such efforts included the following:

- Greyhound offered one bus from St. Petersburg to Clearwater, Dunedin, and Tarpon Springs just once a day.

- Gulf Coast Motor Line provided trips from Clearwater to St. Petersburg, as well as New Port Richey and Tampa.

- Indian Rocks Transit ran a single bus from Indian Rocks Beach to Clearwater.

- Pinellas Park Transit operated five buses to St. Petersburg.

- Clearwater Transit Company, which ran to Largo and Dunedin from Clearwater, worked closely with their neighbors at Gulf Coast Motor Line.

- Pass-A-Grille Beach had its own bus line that served the entire gulf beach area from Redington Shores to Pass-A-Grille, with routes to Willams Park.

- Tarpon Springs Transit Line continued to serve the Sponge Exchange until its termination in May 1959.

A Gulf Coast Motor Line bus, c. 1950’s

(PSTA Archives)

With all of these small bus lines springing up, it was only a matter of time until someone had the idea to combine them. Of course, it would be no easy task, but St. Petersburg entrepreneur Byron Shouppe had to start somewhere. He started by purchasing Southern Tours, a sightseeing and tour bus service based in St. Pete. When the Pass-A-Grille Bus Line went up for sale in 1958, and no one seemed interested, Shouppe made an offer. Sure, it required replacing the old bus fleet, which he negotiated with Miami Transit to purchase ten new buses, but his new Gulf Beach Transit line was beginning to take shape.

When the Pinellas Central Bus Lines contract was expiring, the City of Pinellas Park offered it to Shouppe. There was some drama between Shouppe, the city, and the original owner, but Shouppe prevailed and even extended the bus line. Within a few years, Shouppe purchased the Gulf Coast Motor Line as well.

Meanwhile, Clearwater Transit Inc. and its co-owners, John W. Rowe and William Wightman, obtained franchise agreements with the City of Clearwater in 1958, running 80 routes between Clearwater, Dunedin, and Largo.

A Clearwater Transit Inc. bus, c. 1950’s

A Clearwater Transit Inc. bus, c. 1950’s

(PSTA Archives)

Although these individual bus lines provided something to North and Mid County, South County and St. Petersburg remained the only areas with reliable bus service from SPMTS. The 50s and 60s saw the completion of several integral transportation projects: the Sunshine Skyway Bridge, the Howard Frankland Bridge, the Pinellas Bayway, the Clearwater Pass Bridge, and the last section of US 19 finally reached St. Petersburg, providing a direct path from Pinellas County to Tallahassee.

Pinellas County was no longer isolated from the rest of the state, and the population was rapidly growing, with 1,000 new residents arriving per week. However, there was still no county-wide transit system, leaving two-thirds of the population with no public transit.

The truth was that private bus lines just wouldn’t cut it anymore. And the road to addressing this issue would be a long one.

Trouble in Transit

SPMTS fell on hard times throughout the 60s, as ridership dropped and the agency experienced large consecutive operating deficits. It was becoming a vicious cycle: there weren’t enough riders to pay enough in fares, which would allow investment in better service and buying better equipment to attract more riders. By 1967, SPMTS was nearly $100,000 in the red ($956,048 in today’s money), and the system was so bad no one would ride unless they absolutely had to. And who could really blame them? It wasn't the most pleasant ride, with many vehicles desperately needing repairs and all buses lacking air conditioning to fight the Florida heat.

SPMTS bus, c. 1963.

SPMTS bus, c. 1963.

(PSTA Archives)

And this problem wasn’t unique to SPMTS—the privately owned bus line companies in Pinellas faced similar issues. Byron Shouppe’s transit operations had unionized in 1962 and were on strike in 1967. Shouppe’s bus lines saw too few passengers, and he was forced to apply to the Florida Public Service Commission to increase his fares, which was approved as a temporary measure. Clearwater Transit was also facing similar struggles.

The truth was that most Pinellas County residents preferred their automobiles despite the problems they caused, such as heavily congested highways, clogged local roads, parking shortages, and air quality issues. Most buses lacked air conditioning and were falling into disrepair. Operating costs continued to skyrocket.

And these same issues were happening in cities throughout the entire United States.

Many began to question whether mass transit via buses was viable at all, and it wasn’t just critics. Even the Clearwater Transit Company manager claimed that mass transit was a “sick industry” as he watched his transit system struggle between spiraling costs and dwindling ridership.

Pinellas County officials knew they could only solve these issues with federal and state funding. Two Clearwater City Commissioners, George Brumfield and Don Williams, believed that a single, unified bus system for the county, supported by public funds and cash fares, was the only solution to Pinellas’ transit problem.

Local and Federal Funding to the Rescue

Thankfully, the federal government was not blind to the serious issues plaguing public transportation throughout the nation.

In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed an act that created the Urban Mass Transportation Administration (UMTA), later renamed the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) we know today. UMTA was tasked with providing federal assistance for mass transit projects nationwide. The administration created a Capital Grants Program, which provided $375 million in transit capital assistance over three years. This program required comprehensive regional transportation plans for any grant requests after July 1965, hoping that such requirements would lead to better-organized planning for transit projects.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964.

(Photo courtesy of the Federal Transit Administration)

However, there was a catch—private companies could participate if contracted through a public agency, but only public agencies could actually apply and reap the benefits of federal funding.

In light of this exclusion for private transit companies, the City of Clearwater began to reconsider its franchise with the Clearwater Transit Company and entertain the possibility of forming a new, publicly-funded transit agency. City and county leaders knew their only chance of receiving federal funding would depend on a genuine effort to transport people between Clearwater and St. Petersburg, a dire need that had persisted for decades. It was also clear that public sentiment about public transit would never change until the issue was finally addressed.

In 1967, the aforementioned Pinellas County official George Brumfield began publicizing the desperate need for better transit in the central section of Pinellas County, focusing on a proposed direct “rabbit run” between Clearwater and St. Petersburg. The following year, Brumfield was appointed as a Pinellas County Commissioner and convinced his fellow commissioners to create a Central Pinellas Transit Committee, which he served as its head. By partnering with the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council, Brumfield continued heavily pushing the idea of an improved central Pinellas system, funded by federal grants and matching funds.

A study was conducted to confirm this need, and the 1970 report stated, “Transit service must not only be preserved for Central Pinellas, it must be improved. It must become more responsive to the needs of Central Pinellas citizens and grow with their needs and desires. This cannot be accomplished by a repair of the current system’s physical and fiscal situation; extraordinary measures may be necessary to provide a transit system which can serve travel needs and not place a burden on community resources.”

Following the report, the Central Pinellas Transit Committee formally requested that the Florida Legislature create a new transit agency. By August 1970, legislation passed, and the Central Pinellas Transit Authority (CPTA) was created.

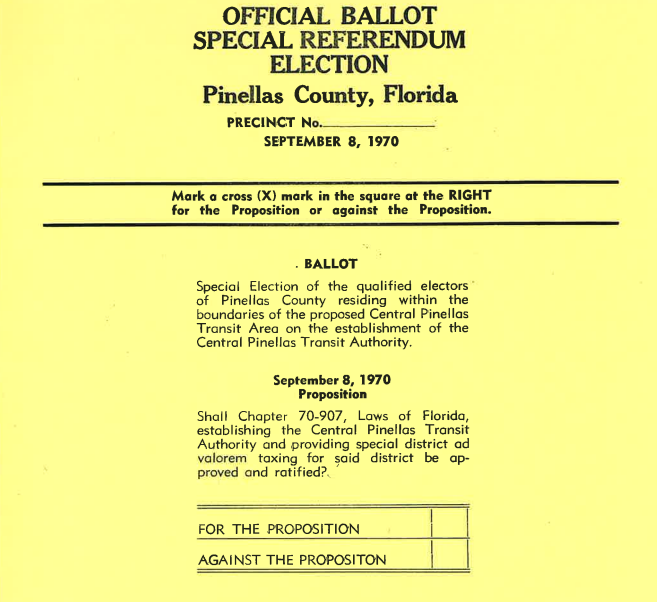

A voter ballot for the legislation that would create CPTA.

A voter ballot for the legislation that would create CPTA.

(PTSA Archives)

However, the new transit authority would still be subject to a voter referendum for approval of the agency’s implementation. And things were a little rocky right out of the gate. As the Central Pinellas Transit Committee worked on a grant proposal for federal funds to get their new agency off the ground, voters vetoed the proposal for a .25 millage ad valorem tax to support the new bus system beyond its start-up, slashing the brand new agency’s local funding.

The reality was that although the public strongly supported the idea of an improved transit system, they did not support the idea of having to pay for it. Without the approval of public funding, CPTA would go nowhere. And neither would the grant proposal, which depended on public subsidy.

While CPTA sought solutions for their failed referendum and toiled over their grant proposal, the agency would take over the struggling Clearwater Transit Company to maintain local services. Over the next two years, public opinion shifted as people began to understand that 25-cent fares could not possibly sustain a transit system with no public funding. By December 14th, 1971, the referendum passed, and CPTA would receive its funding.

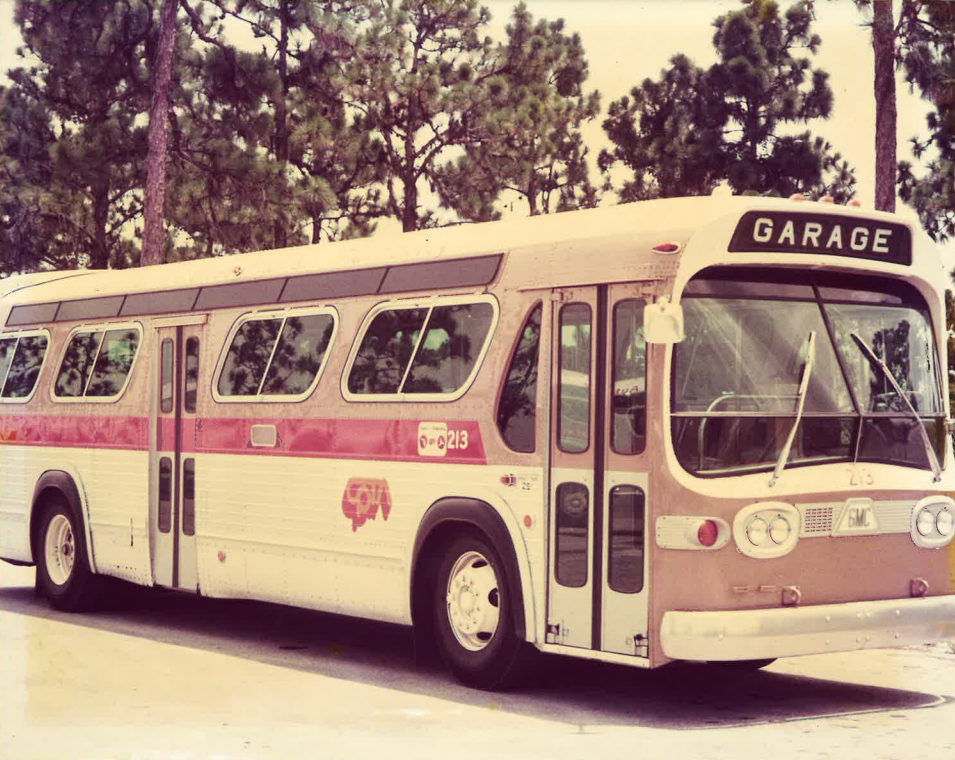

And, at last, February 1972 would finally see CPTA’s very first UMTA capital grant of $983,149 ($7,487,643 in today’s money). This funding allowed CPTA to purchase 21 new air-conditioned buses, fare boxes, garage space, office space, ten passenger shelters, and a privately owned bus company. CPTA finally had what it needed to launch the much-needed transit services in Mid- and North-County Pinellas.

A new CPTA bus, c. 1970s

A new CPTA bus, c. 1970s

(PSTA Archives)

A Tale of Two Transit Agencies

We’re so close to the genesis of PSTA, you can almost taste it!

The shiny new Central Pinellas Transit Authority (CPTA) and the old faithful St. Petersburg Municipal Transit System (SPMTS) would spend the next decade or so operating simultaneously in Pinellas County. CPTA would manage North and Mid County, while SPMTS would serve South County. However, the two transit agencies would become inexplicably linked over the years, working together to help Pinellas County residents easily travel throughout the county.

An SPMTS patch and a CPTA token.

An SPMTS patch and a CPTA token.

(PSTA Archives)

But we still have a way to go until the two transit agencies finally combine to create the Pinellas Suncoast Transit Authority we know and love today!

CPTA Begins

New CPTA logo.

New CPTA logo.

(PSTA Archives)

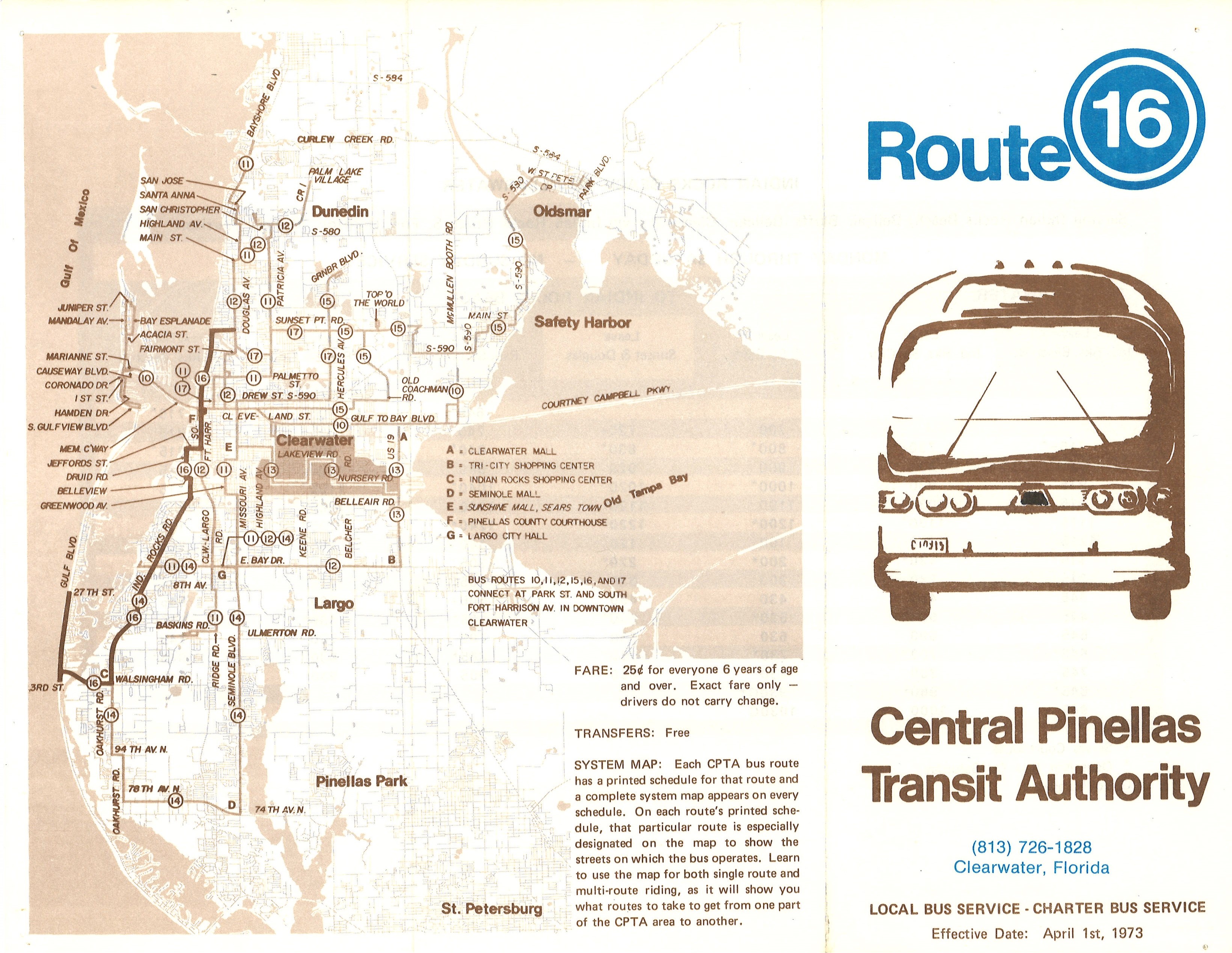

On April 16th, 1973, CPTA began service with 21 buses running along nine routes in eight cities. However, it was not the easiest start for the burgeoning new agency. The first bus began service at 6:30 am and CPTA had its first vehicle accident at 7:10 am. By 9:00 am, one of the new bus operators decided the job wasn’t for him, left the bus at the curb, and was never seen again.

A rocky start, to say the least.

But CPTA barrelled on through its early growing pains, gaining positive press coverage and steadily increasing ridership. With its clean, well-maintained buses sporting blessed air-conditioning, widespread access to schedules and maps, reliable telephone information, and good-natured bus operators, CPTA’s services were a breath of fresh air (literally!) after the downward spiral of the 60s. Its first year of operation saw 900,000 passengers and, soon enough, other cities and county areas were requesting to be included. Such requests led to three more successful referenda that expanded CPTA’s service area with full tax support.

One of the first CPTA route schedules, April 1st, 1973.

One of the first CPTA route schedules, April 1st, 1973.

(PSTA Archives)

A five-year program was developed, allowing the agency to acquire additional buses each year. After obtaining another UMTA grant of $875,000 ($6,212,697 in today’s money), CPTA purchased 14 more buses and radio network communications.

By 1976, service to Tarpon Springs had begun, and CPTA’s service area would eventually extend from the city limits of St. Petersburg to Pasco County. The agency’s promise to serve Central and North Pinellas County was slowly but surely fulfilled.

A CPTA bus operator dressed as Santa Claus, c. 1970’s.

(PSTA Archives)

SPMTS Struggles

While CPTA was flourishing, the St. Petersburg Municipal Transit System (SPMTS) was struggling. Throughout the early 70s, the agency was at a $1.6 million annual deficit and had to be subsidized by additional money from the City of St. Petersburg. SPMTS had become the “whipping boy” of the city’s transportation department, frequently criticized for losing money and failing to provide adequate transit services.

However, with the new reality of grants and local funding, the City Council determined that SPMTS didn’t need to be profit-oriented. Instead, changes were made to better serve the public’s needs; routes were changed to more attractive destinations like shopping malls and other entertainment venues. Transfer fees were finally eliminated as new bus passes were introduced.

An SPMTS bus accepting passengers bound for Gateway Mall.

An SPMTS bus accepting passengers bound for Gateway Mall.

(PSTA Archives)

In 1971, SPMTS made its first attempt to provide specialty services for the elderly and individuals with disabilities through a program called Transporation for the Elderly (TOTE), funded by a UMTA development grant. The program would provide door-to-door service in a small area of downtown through the use of van-style vehicles, making it the county’s first paratransit service (a service for individuals with disabilities). And the program was a modest success, providing services to 10,500 passengers per month. By 1975, TOTE was replaced with Dial-A-Ride or DART, which provided that same door-to-door service for the elderly and individuals with disabilities, but now on a city-wide scale.

A DART operator helping a customer with a mobility aid onto a DART van. While this photo shows the PSTA-operated DART program, the SPMTS program worked the same way.

(PSTA Archives)

The 70s also brought the trend of transportation nostalgia, with many cities running trolley and streetcar-style buses in high tourist areas—and St. Petersburg would follow the trend. SPMTS would introduce 30 cable car-style trams to supplement its service, reminiscent of the San Francisco cable cars. The service launched on April 10th, 1978, and served the waterfront, central business district, and pier areas.

SPMTS cable car bus passing The Princess Martha, which was a hotel at the time.

SPMTS cable car bus passing The Princess Martha, which was a hotel at the time.

(PSTA Archives)

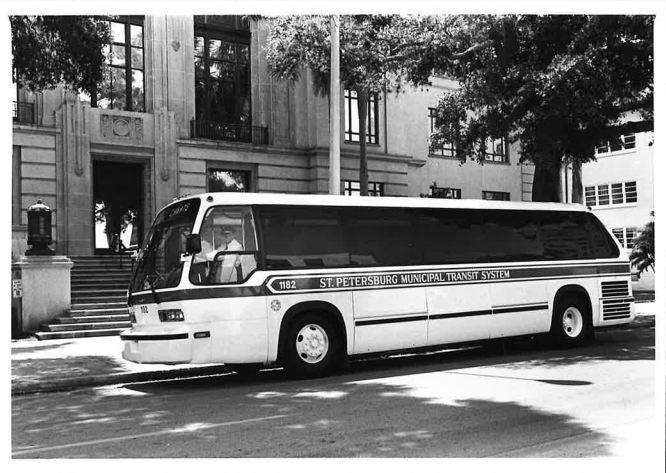

Transportation planning was now focusing more on the availability of federal and state subsidies, so SPMTS set its sights on applying for more grants to heave itself out of hard times. In 1976, SPMTS would receive a $640,000 UMTA grant ($3,525,492 in today’s money), allowing for the purchase of ten brand new 45-seat GMC buses that would finally offer air-conditioned public transit to its riders.

The Energy Crisis

As we discuss the 70s, it’s time to address the transit elephant in the room: the energy crisis.

Technically, there were two crises in the 70s: one in 1973 and another in 1979. Caused by an oil embargo due to conflict in the Middle East, nationwide gas shortages and skyrocketing costs were putting a major strain on automobile owners as gas stations quickly ran dry.

Dozens of vehicles line up in hopes of getting gas during the nationwide shortage.

Dozens of vehicles line up in hopes of getting gas during the nationwide shortage.

(Courtesy of NPR.)

Transit systems throughout the US, including SPMTS and CPTA, certainly felt the strain of the gas shortages… but they also saw an increased demand for their services. It was a unique situation, as this demand would increase ridership but forced some unequipped agencies to spiral downward, unable to meet the needs of their riders.

And how did our two local agencies fare? It was a mixed bag.

While more people choosing to ride transit was a net positive on paper, both transit systems faced the same challenges as individual motorists and struggled to meet their needs. Just as gasoline was in short supply, so was diesel. Fuel rationing, reminiscent of WWII, had taken effect, and both agencies were forced to reduce services and fuel consumption. Fares increased to cover escalating fuel costs. Gulf Beach Transit, one of the few private transit companies left in Pinellas County, ceased operations. SPMTS ran out of subsidies. For South County transit, things were rough.

A St. Petersburg Municipal Transit System Bus in front of St. Petersburg City Hall.

A St. Petersburg Municipal Transit System Bus in front of St. Petersburg City Hall.

(PSTA Archives)

CPTA fared a little better, however, as ridership increased rapidly. April 1973 saw 64,000 passengers, with that number doubling within nine months as the fuel shortage set in. By 1978, the agency was carrying 2.25 million passengers per year.

It was a challenging time for our two transit agencies. Over the next five years, CPTA and SPMTS would muddle through by adjusting routes and schedules, fixing older buses rather than replacing them, cutting down the number of stops, and hiring more temporary drivers to keep costs low. Both agencies forged partnerships with the county’s largest employers to bus their employees to and from work during the worst of the shortage.

A Central Pinellas Transit Authority bus.

A Central Pinellas Transit Authority bus.

(PSTA Archives)

The services weren’t pretty; absent were the days of pleasure routes and shopping mall destinations, but the routes were serviceable enough considering the critical conditions of the shortage. And eventually, the crisis would end and take its increased ridership with it as people returned to their cars.

However, the difficult times had led to a new camaraderie between CPTA and SPMTS as they weathered the fuel shortages together. Discussions of integrated services began despite the fact that nearly every aspect of the two agencies was vastly different: separate boards, separate unions, separate fare structures, separate buses, and separate rules.

Undeterred, the two agencies finally created the long-awaited St. Petersburg to Clearwater route. Both agencies began honoring each other’s half-fare cards for the elderly in 1977. At the start of 1980, CPTA and SPMTS introduced an intersystem transfer program, common fares, and a common information phone number for assistance.

Things were changing in Washington, too.

In reaction to the energy crisis, Congress passed the Mass Transportation Act of 1974, allowing federal funds to be used for operating subsidies. It also introduced a new requirement that each metropolitan area examine the merits of a single transit system. Funding eligibility would favor one system, not two.

Perhaps a merger was just what Pinellas County needed.

The Merger

The idea of merging CPTA and SPMTS was not new. Some transit advocates had been suggesting it for years. However, with the changes in federal funding eligibility and the fresh memory of fuel shortages, county officials began seriously considering the merits of an official merger.

In 1976, a new federal law led to the creation of Pinellas County’s Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO). Not only would this MPO provide countywide transit planning and become a forum for cooperative decision-making, but it would also be the designated recipient of state and federal funds for public transit in Pinellas County.

By 1980, unifying the two transit systems was in serious discussion. Considering the two systems were already coordinating their services with each other, regular exploratory meetings began to take place. The MPO established a committee to study the unification, aptly called the Citizens Transit Unification Committee, of which its members included CPTA board members, city council members, and Chamber of Commerce representatives. Considering how interwoven the agencies had already become and the promising results of studies conducted on the topic, it was only a matter of changing the legislation to make the merger official.

While steps were already underway to integrate the two agencies, transit leaders looked towards the upcoming legislative session with hopes that the law that created CPTA could be amended. As it stood, the law did not include representation for St. Petersburg and Pinellas Park. Even more important (and controversial) was the provision that proposed a raise in the .25 millage cap to .75 (spoiler alert: .75 is the current millage cap rate today). While it would be a tough sell, it was Pinellas’ best hope for a firm mass transit solution.

On April 26th, 1982, House Bill 842 created the Pinellas Suncoast Transit Authority (PSTA) to replace Central Pinellas Transit Authority (CPTA). PSTA would serve the areas already within CPTA’s pre-existing service area, with the new inclusion of St. Petersburg, along with provisions to include other municipalities in the future. At last, one unified system would have total control of the county’s public transportation.

However, there was still the referendum. Voters still had the right to approve the merger and the millage increase, regardless of the House Bill. And the referendum was eventful, to say the least.

A promotional flyer for the referendum that would merge the newly named PSTA and SPMTS into one transit system.

A promotional flyer for the referendum that would merge the newly named PSTA and SPMTS into one transit system.

(PSTA Archives)

On October 5th, 1982, the referendum was split. Voters in Mid and North County, the area already served by the new PSTA, turned down the proposed merger, while St. Petersburg voters approved the measure. As it turns out, voters in North and Mid County were somehow provided with a ballot that only asked for the approval of a tax increase without explaining the merger at all.

It was, to be blunt, a mess.

PSTA leaders and attorneys immediately looked into holding a special election and began ramping up a massive marketing campaign to help the public understand the purpose and benefits of the merger. An impressive $53,000 in radio and TV advertisements began, citizen advocates sent letters, and action committees spoke with the club circuit. PSTA’s leaders and supporters were determined to make their case and win the public over. It certainly didn’t hurt that, two weeks before another referendum vote would occur, UMTA presented PSTA with the prestigious 1983 UMTA Award for Outstanding Public Service. The news would garner even more positive press and public sentiment.

A St. Petersburg Times Article discussing the November vote for the merger, July 20th, 1983.

A St. Petersburg Times Article discussing the November vote for the merger, July 20th, 1983.

(PSTA Archives)

On November 8th, 1983, it was “take two” for the referendum, and the merger was finally approved with a vote of 16,152 to 11,750. As the clocks rolled over to 1984, the merger of two mature transit systems was completed, a feat never before accomplished in transit history.

Pinellas Suncoast Transit Authority would become Pinellas County’s sole publicly funded transit provider.

Next Stop: Pinellas Suncoast Transit Authority

Congratulations, you finally made it to the PSTA era!

In the next and final part, we will dive into the history of PSTA itself and the rapid acceleration of services and transit technology. And, for many of you, the 80s, 90s, and 2000s vibes will bring a healthy dose of beloved nostalgia.

Click here to continue the story!

Sources

Buckley, James. Street Railways of St. Petersburg, Florida. Harold E. Cox, 1983.

Elftmann, Steve. The Jungle Country Club History Project, junglecountryclubhistoryproject.blogspot.com/p/blog-page.html.

Florida Memory, www.floridamemory.com/.

Kile, Monica. “125 Years of Light and Power in St. Petersburg.” I Love the Burg, 17 July 2024, ilovetheburg.com/125-years-of-power-and-light-part-two/.

Kile, Monica. “Remembering St. Pete’s Long-Lost Trolleys.” Northeast Journal | St. Petersburg, Florida Journal | Newspaper, 24 Jan. 2023, northeastjournal.org/remembering-st-petes-long-lost-trolleys/.

Lehman, Robert. “Streetcars in Tampa and St. Petersburg: A Photographic Essay.” Tampa Bay History, Digital Commons @ University of South Florida, 1997, digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1442&context=tampabayhistory.

“Pinellas County Historical Background.” Pinellas County, Dec. 2008, pinellas.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/PCHB.pdf.

Stanton, Robert A. Streetcar to the Jungle: Trolleys in the Streets of St. Petersburg, Florida. 2006.